Exhibits Labor and the NAEB

Organized labor and educational broadcasters often found common cause in the US. Educational broadcasters feared commercial interests would dominate radio and later television, and displace their vision of broadcasting as an instrument for edification and enlightenment with one that imagined it as a technology for entertainment and profit. Unions saw in commercial broadcasting an existential threat, constituted by a pro-corporate orientation that, utilizing the most powerful form of communication, could inculcate business values as neutral, demands for workers’ rights as radical. Along with others, unions and educational broadcasters joined forces in the late 1920s and early 1930s to resist a regulatory paradigm that favored commercial radio. One of the resolutions passed at the first meeting of the newly merged American Federation of Labor (AFL)-Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) union was in support of the continued expansion of educational television.

Yet, as documents surfaced through Unlocking the Airwaves reveal, the relationship between organized labor and educational television extended beyond forms of mutual solidarity. In the 1950s and 1960s, as educational television stations went on the air in communities across the country, the noncommercial television sector had to negotiate relationships with trade and talent unions and to discern how and to what degree labor would factor into the imagined public that educational stations would serve. Morris Novik was critical to both projects.

Who is Morris Novik?

Novik was born in Russia and immigrated to the US at age eleven. At a young age, he became involved in politics, writing for socialist newspapers and magazines and serving as president of the Young People’s Socialist League (Godfried 350). He directed both the Unity House, a summer resort run by the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union and, from 1928 to 1931, the Discussion Guild, which provided public lectures and debates between leading public intellectuals. In 1932, Novik took over as the program director for WEVD. Named after socialist leader Eugene Debs, WEVD was imagined as a “forum for liberal, progressive, labor and radical purposes, and not merely and solely as a Socialist Party enterprise” (Godfried 348).

Under Novik’s leadership, WEVD launched a “University of the Air,” which featured experts on a range of topics and addressed issues important to working-class New Yorkers. In addition, at WEVD Novik corrected what he saw as one of the failures of the station’s initial management: he actively cultivated relationships with organized labor and encouraged its participation in station programming (Godfried 353-57). At WEVD, Novik evinced a commitment to educational programming while also airing sponsored, non-English language entertainment to pay the bills. As Brian Dolber (2013) notes, this mix meant that listeners were alternately addressed as members of a working class and as members of distinct ethnic enclaves.

Novik left WEVD in 1938 to become the manager of WNYC, the municipal radio station in NY. Under Novik, WNYC innovated in both informational and cultural programming. During World War II, it dedicated approximately half of its programming to explain, inform, and encourage support for the war effort. It also inaugurated the American Music Festival, which provided live music from concert stages across the city and broadcast, in Novik’s phrase, “drama with a purpose,” including plays about racial prejudice. Novik left WYNC in 1946 to become a public service consultant to commercial broadcasters and as a radio consultant to the AFL.

Novik, Labor Advocacy, & the NAEB

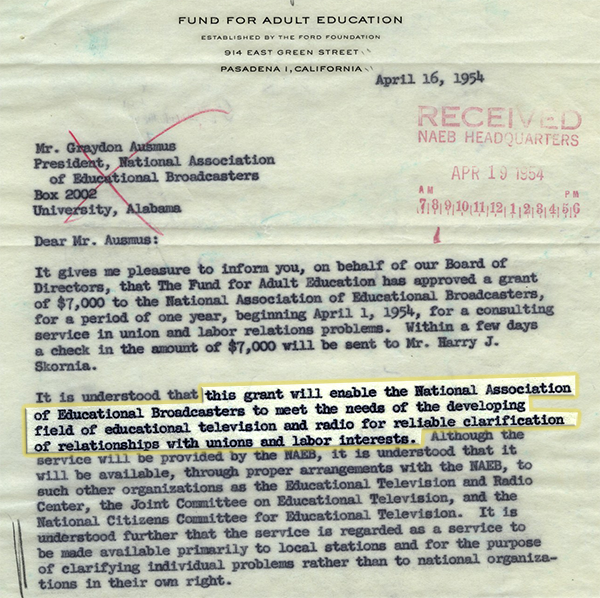

Novik joined the NAEB in 1939. He served on the NAEB’s Board of Directors from 1939 to 1945. In 1946, he was appointed the NAEB’s Executive Secretary, a role he filled until 1948 (Hill 57-59). In 1953, NAEB Executive Director Harry Skornia approached Novik about working as a consultant for the NAEB to help local educational television stations with labor relations.

The previous year, the Federal Communications Commission had reserved 242 frequencies for noncommercial educational television. Subsequently the NAEB, along with a range of other national organizations, worked to assure the growth of educational television, by drumming up popular support for a noncommercial television sector, advocating for policies conducive to its continued development, and providing aid – technical, legal, tactical – to local stations. Novik’s position as the NAEB’s Management and Community Relations consultant, which was codified in 1954 a grant from the Ford Foundation’s Fund for Adult Education, was consistent with these practices.

Novik’s work would be coordinated through the NAEB Executive Director’s office; he would assist local stations in negotiating relationships with unions and work with other national organizations, especially the Educational Television and Radio Center (ETRC), to navigate rights for nationally circulating programming.

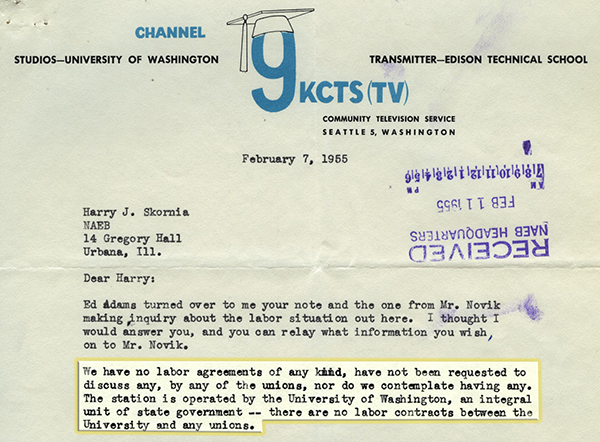

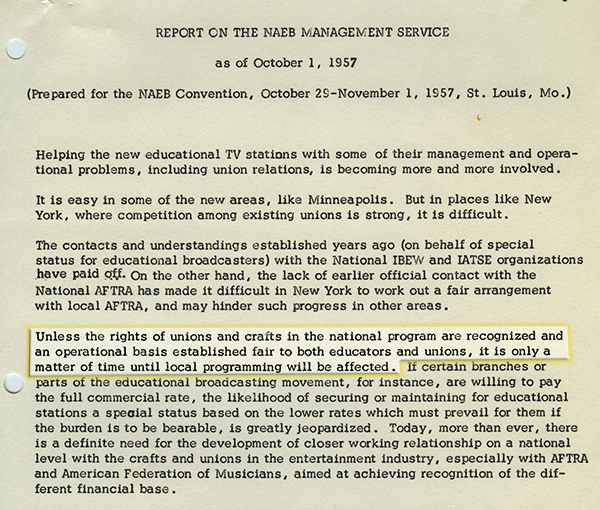

The issues around unions and the educational television sector were multiple and thorny. The sector in the 1950s encompassed a heterogeneous range of stations; some were controlled by universities or public-school systems, others by state commissions, and still others by community organizations. Some were located in right-to-work states, while others were in strong union cities. Some envisioned educational television as instructional television, others an instrument of adult education, cultural uplift, or counter-programming to commercial stations. Accordingly, not all stations employed represented workers – some, like KCTS in Seattle, were run by a public university and staffed by students and college personnel – and stations varied in their support of organized labor.

Given this diversity, stations insisted that labor negotiations should be exclusively local, responsive to local conditions, and not applicable to the sector on whole. As Skornia relayed to Novik, station managers were “afraid that in many areas where there’s no trouble, a national agreement would be a disadvantage.” So much of Novik’s work was on a station-by-station basis and drew on his longstanding relationships with labor leaders.

Most educational television stations operated on very small budgets, especially in comparison to commercial telecasters. Their budgets foreclosed their ability to pay represented workers the same wages they received at commercial stations. As Richard Goggin, station manager of KETC in St. Louis, wrote to Novik in December 1953, “no educational television station can financially face a future in which everyone on staff is unionized at union commercial television pay scales. We are now at a crucial point.”

Accordingly, a key service that Novik provided to stations was educating union leaders about the mission, function, and finances of educational television stations. He successfully persuaded many unions, especially those representing technicians, to forego the rates they charged commercial stations and adopt lower rates for educational stations. He also supported stations who were at the center of turf battles between locals and, importantly, advised stations to work fairly and honestly with local unions.

This was a crucial facet of Novik’s work. On the one hand, he sought advantageous labor contracts for local stations, and on the other hand he insisted that educational television respect the rights of organized labor and its import in local communities. He encouraged newly licensed stations to build relationships with local unions, appoint union leaders to station boards of directors, and coordinate with unions to build community support for the station. Not only would such actions forestall future labor strife but, for Novik, they also would assure that the interests of workers were central to the mission of educational television.

Educational TV & Labor after the Taft-Hartley Act

The educational television sector took shape in the years following passage of the Labor Relations Act of 1947, also known as the Taft-Hartley Act. Taft-Hartley, as Nelson Lichtenstein (2003) has written, “sought to curb the practice of interunion solidarity, eliminate the radical cadre who still held influence within trade union ranks, and contain the labor movement to roughly its existing geographic and demographic terrain” (Lichtenstein 390). The law not only curtailed how, where, and for whom unions could operate, but it ejected the political left from the labor movement and radically circumscribed its ambitions. While Taft-Hartley did not augur the death knell of the labor movement, it did instantiate a new phase of, in Lichtenstein’s (2002) phrase, “trade-union parochialism” that “penalized any serious attempt to project a classwide political-economic strategy”(122).

The educational television sector also took shape in the wake of the demise of union-run FM radio stations. As Elizabeth Fones-Wolf (2008) has illuminated, in the late 1940s and early 1950s, these nonprofit stations sought to provide public interest programming that made forms of high culture accessible to a wider public, reflected the diversity of local communities, provided space to issues and viewpoints erased from commercial broadcasts, and highlighted union activities and workers’ struggles. By 1952, all these stations had gone off the air, primarily because of financial losses. Subsequently, and with the guidance of Novik, unions would produce and sponsor broadcasts on commercial AM stations to reach its members and the broader public in the 1950s.

Novik’s work for the NAEB occurred against this backdrop, in which the transformative potential of the labor movement had been curtailed legislatively and the voices of labor on the airwaves had been diminished substantially. Though he was hired to help stations negotiate advantageous agreements with local unions, he used his position to propel a goal he had pursued throughout his career: to assure that workers, and the unions that represented them, were respected and were seen as crucial members of broadcasters’ publics.

Works Cited and Further Reading

Dolber, Brian. “Strange Bedfellows: Yiddish Socialist Radio and the Collapse of Broadcasting Reform in the United States, 1927-1938,” Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television 33, no. 2 (2013): 289-307.

Dolber, Brian. “Unmaking ‘Hegemonic Jewishness’: Anti-Communism, Gender Politics, and Communication in the ILGWU, 1924-1934,” Race, Gender & Class 15, no. 1/2 (2008): 188-203.

Fones-Wolf, Elizabeth. “Broadcasting Unionism: Labor and FM Radio in Postwar America.” In Radio Cultures: The Sound Medium in American Life, edited by Michael C. Keith, 151-170. New York: Peter Lang, 2008.

Fones-Wolf, Elizabeth. Waves of Opposition: Labor and the Struggle for Democratic Radio. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2006.

Godfried, Nathan. “Struggling Over Politics and Culture: Organized Labor and Radio Station WEVD During the 1930s,” Labor History 42, no. 2 (2001): 347-369.

Godfried, Nathan. WCFL: Chicago’s Voice of Labor, 1926-78. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1997.

Hill, Harold E. The National Association of Educational Broadcasters: A History. Urbana: NAEB, 1954.

Lichtenstein, Nelson. State of the Union: A Century of American Labor. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2002.

Lichtenstein, Nelson. “The Unions’ Retreat in the Postwar Era.” In Major Problems in the History of American Workers, edited by Eileen Boris and Nelson Lichtenstein, 384-396. Boston: Wadsworth, 2003.

McChesney, Robert W. Telecommunications, Mass Media, and Democracy: The Battle for the Control of U.S. Broadcasting, 1928-1935. New York: Oxford University Press, 1993.

Allison Perlman is an Associate Professor in the Departments of History and Film and Media Studies at the University of California, Irvine. She is the author of Public Interests: Media Advocacy and Struggles Over US Television (Rutgers UP, 2016), which won the Outstanding Book Prize from the Popular Culture Division of the International Communication Association. She is currently writing a history of National Educational Television (NET). In addition, she and Josh Shepperd are revising The History of Public Broadcasting for the Corporation of Public Broadcasting. She has served in leadership roles for the Library of Congress’ Radio Preservation Task Force and currently is the co-chair of the Scholars Advisory Committee for the American Archive for Public Broadcasting.

.](/static/09fd3cfe3159d359e40f00426ece75e2/52183/naeb-b067-f02_0158-crop.png)

Portrait of Morris Novik at the head of a Broadcasting Magazine piece entitled ‘Labor Turns to Radio.' Read the entire piece at the Unlocking the Airwaves website.

."](/static/0d05e54741813c05d9894b06dad5d1ac/99c3d/mnovik_egoldberger_election-wnyc.jpg)

Morris Novik and the WNYC election night news team circa 1941. Photo courtesy of WNYC Archive Collections, from the feature piece "Morris S. Novik: Public Radio Pioneer."