Exhibits Dance on the Radio: An Exploration of Dance Programs in the BAVD Archives

“Dancing about architecture” is not the ridiculous idea that the old joke asserts. Like architecture, dance is visual and spatial: the 3-D arrangement of forms in conversation with a context, the shaping and channeling of the human body, the aesthetic and practical unfolding of patterns of movement over time. From that perspective, dance is architecture, just sped up and with a different soundtrack.

Now, “radioing about dance”: that would be ridiculous, right? After all, the visual and the spatial are two dimensions that radio famously lacks. Surely, dance has to be seen to be appreciated, so dance and radio ought to be antithetical.

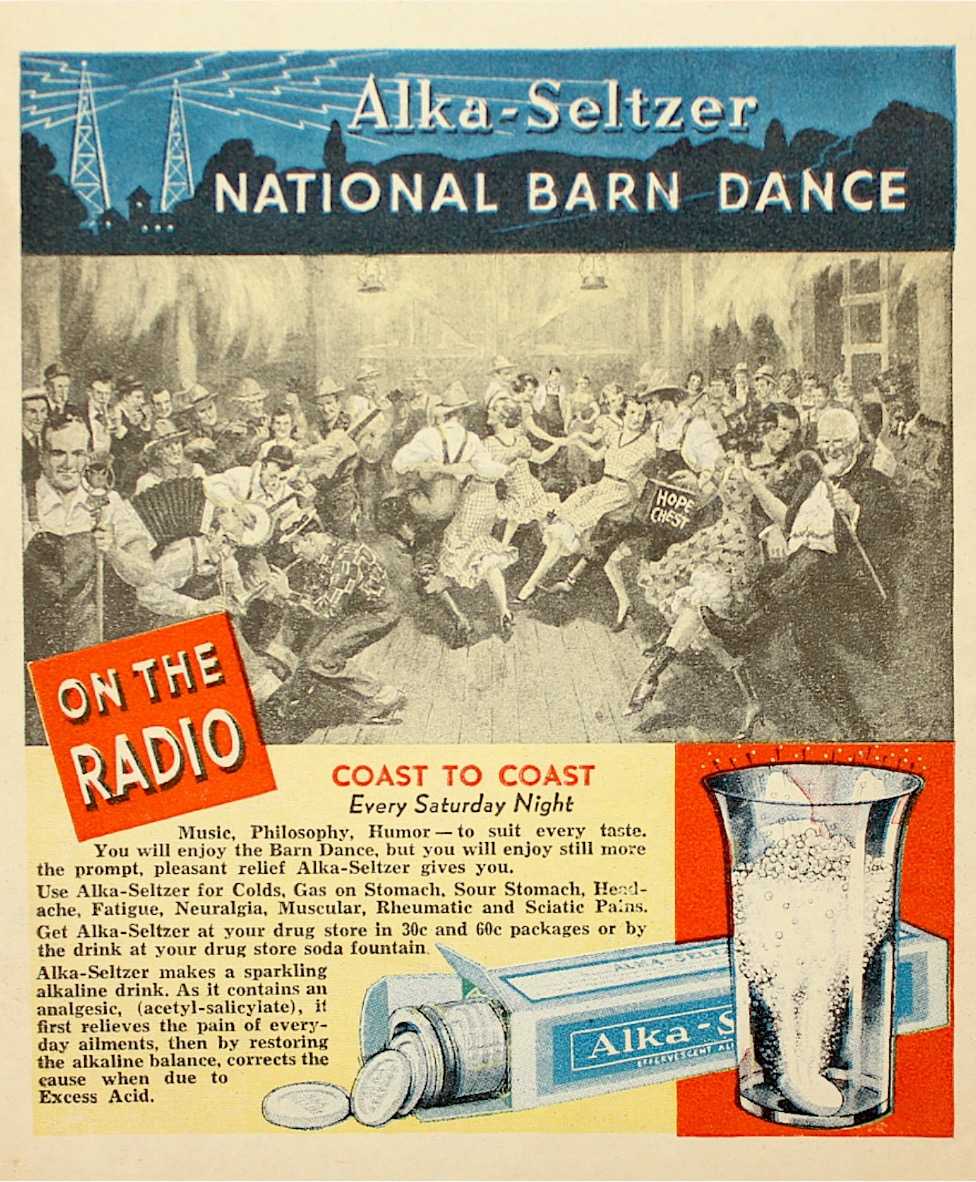

But even that distinction falls apart quickly. Indeed, one of the very first blockbusters of broadcasting named “dance” in its title: WLS’s National Barn Dance, which hailed listeners as an exuberant community of dancing fools in a great big old hoedown. Since then, radio has conjured the suave dancer at the hotel ballroom, the energetic teen at the sock hop, the sinuous bumper at the discotheque—encouraging listeners at home to join in a communal fantasy and also dance. Though all of the dancers may have been unseen, dance has been integral to radio’s programming for over a century, not to mention to radio’s sense of liveness and its modes of invitational rhetoric: “Come on, everybody, get up and DANCE!”

Radioing about dance, then, turns out to be a complicated phenomenon, and the archives available through Broadcasting A/V Data reveal radio’s participation in constructing the cultural place of different forms of dance, as well as dance’s participation in constructing different forms of radio.

Here, the commercial/non-commercial radio and low/high art distinctions are key. Dance is a continuum, from the simplest toe-tap to the most demanding grand jeté, upon which genres and categories like “low” and “high” must be imposed and enforced. In the U.S. at least, ballet and modern dance have largely been hived off into the category of “high art,” putting dance into a tense relationship with radio: a few classical stations notwithstanding, American commercial radio has consistently been shaped by its populism and embrace of “low” cultural forms, shunting programming “for elites” to the edges of the schedule. Furthermore, radioing about dance really does push against the limitations of the medium when it comes to ballet and other and forms of “art” dance: the participatory mode of radio address that works for more popular dance forms would seem ludicrous for a Martha Graham piece, and while it might be possible to call Swan Lake for radio like a baseball game, I’m guessing it has never been seriously tried.

That left non-commercial radio to engage with “high” dance forms like ballet and choreographed modern dance, and these archives reveal their co-constitutive relationship: public and educational radio found meaning and mission in addressing cultural forms that commercial radio wouldn’t touch, and those cultural forms retained their cachet by becoming intellectualized and pedagogized on non-commercial radio. Furthermore, the emphasis on networks here foregrounds the ways that relationship evolved over time.

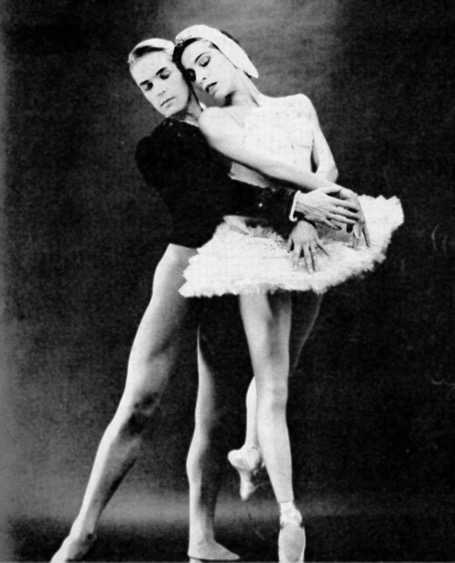

Take, for example, Success in the Arts, a program you can explore in the NAEB collection. Hosted by Studs Terkel, well known for his pro-labor sympathies, two 1957 episodes (here and here) center on dance as a form of work. Guests including choreographer George Balanchine, prima ballerina Maria Tallchief, and dance instructor Donna Claypoole detail the hours of literal blood, sweat, and tears required to become a great dancer, situating dance within postwar beliefs about getting ahead by working harder: pulling yourself up by your own pointe shoes, as it were. Thus Balanchine describes dance in competitive terms of striving to be better than the other fellow, and there’s a telling anecdote in which a dancer complains that a move that Balanchine had choreographed was simply impossible to execute, at which point Balanchine—by then well past his dancing prime—got up and performed the move, quickly shutting the dancer up. Similarly, Claypoole highlights the ability of dance to build character and improve a person’s moral fiber through discipline and ceaseless effort.

Importantly, this articulation of high art to high effort unfolded in the context of the Cold War and specifically the “Cultural Cold War,” in which U.S. government agencies promoted American artists globally as symbols of Western political, moral, and cultural superiority. Ballet was particularly consequential here given its associations with Russian history and culture: Russian composers and ballet companies dominated ballet as thoroughly as Russian players dominated international chess.

In this archive, then, you can hear efforts to Americanize ballet and claim the art form for Democracy. Russian methods of ballet training—imagined as a cruel collectivist boot camp of compulsory conformity—are contrasted with American striving toward individual self-expression. Interviewees repeatedly emphasize the necessity of stamping one’s unique personality on a move, the individual dancer’s personal contribution to the overall impression of a piece, and the value of different physiques. Dancer Maria Tallchief, for example, urges girls of varying body types to try ballet: “I don’t believe it should be too discouraging for people who don’t think they’re built like Venus. … You are always able—through work, through a very conscious effort—to make the public believe that you have the most beautiful figure in the world, just through your movement alone.” One should definitely not read any proto-feminist body positivity into Tallchief’s words (especially since her standard remains a “beautiful figure” and she does, in the same breath, rule out girls whom she deems insufficiently slender), but it is noteworthy that Tallchief argues that “success in the arts” comes not from genetics or inborn talent, but rather from “American” values of discipline, hard work, and blinding self-confidence. American ballet, then, is marked as superior by its linkage to American freedoms and values. (Interestingly, one speaker speculated that this freedom of movement that Americans supposedly possess may have something to do with the influence of jazz—a rare but telling injection of race into these conversations about Americanness and dance, and one that will come up again.)

The obsession with the arts as a barometer of American life can be heard most prominently in a talk by choreographer Agnes de Mille and broadcast through the NAEB. de Mille did as much as anyone to “Americanize” ballet through works like her cowboy ballet Rodeo. After some entertaining remarks about her school days and television work, de Mille launches into her main theme: that how we treat the arts is a measure of our own greatness or mediocrity as a society. Explicitly invoking commercial radio through mocking pastiches of its folksy speech and hard-sell ads, she condemns Americans’ failure to support high art as indicative of a broader failure of American character: “Our reliance on authority is paralyzing us. … We are now the conformers, we, we Americans who crossed cold water in wooden ships because we were non-conformist.” Thus, discussions of dance on non-commercial radio become a site for expressing deep political and cultural anxieties about the state of the American soul, especially as it was (supposedly) revealed by commercial radio.

Following the breadcrumbs from the NAEB to the KUOM areas of the collection, we can hear how dance, a few years later on a different network, is implicated in very different questions of social identity: instead of a reflection of an overarching American character, dance has become a site to work through the struggles over differences of race, gender, and sexuality in the 1960s and ’70s. A good example is a 1975 episode of Minnesota School of the Air’s “People Worth Hearing About” that presented a biography of Tallchief, selected because of her Osage heritage. All of the grueling work that Tallchief herself had emphasized in her conversation with Studs Terkel eighteen years earlier has been erased; instead, the episode attributes her success to her aboriginal roots—to the strength and spirituality of Native Americans—and describes Tallchief as motivated less by the beauty and joy of ballet than by the Osage ceremonial dances she learned growing up. “It is said that only the Russian and American peoples have the natural feeling for ballet,” the narrator tells us, by way of implying that Tallchief must, as a Native American, have more of that “natural feeling” than anyone. (The more generous depiction of the Russians is also a sign of changing times.) For the spelunker in the Broadcasting A/V archives, these two representations of Tallchief, two decades apart, reveal a fascinating shift in conversations around Americanness: from a geopolitical value system to an interrogation of identity and difference, all in the context of dance.

Questions of cultural identity are also prominent in a 1975 Minnesota School of the Air interview with Minneapolis ballet dancer Lewis Whitlock III. An African-American male working in a genre closely associated with white femininity, Whitlock speaks candidly about race and gender in his profession, addressing the influence of Black dance forms on his work and noting that boys are discouraged from taking up dance for fear of being labelled a “sissy.” Although the interview is short, it provides a refreshing recognition of the ways that racial, gender, and sexual diversity are policed through the artificial separation of different cultural forms. The fact that such conversations rarely aired on commercial radio further solidifies the ways in which public and educational broadcasting and dance worked together to reinforce non-commercial radio and high art.

Ultimately, such insights are the power of exploring the Broadcasting A/V archives: the chance connections and accidental finds that enrich our understanding of people, topics, and radio itself. I mentioned above that dance is a continuum between the simplest and most complex movement, and between the most popular and esoteric forms. American radio in all of its guises has used dance, but in different ways: separating Barn Dance from Rodeo, and separating us from each other. But radioing about dance also reveals the possibility of finding and connecting with others along that continuum. As Whitlock put it, "There's a rhythm to everything, if you listen. There's a rhythm to the cars moving down the street, to a water faucet. … If you think about walking the right way, it can be dance."

***

Bill Kirkpatrick is Assistant Professor of Sociology at the University of Winnipeg; prior to moving to Winnipeg, he was Associate Professor of Media Studies in the Communication Department at Denison University. His publications include articles in Communication, Culture, and Critique; Critical Studies in Media Communication; Television & New Media; Radio Journal; the International Journal of Communication; and several anthologies. He is co-editor (with Elizabeth Ellcessor) of Disability Media Studies (New York University Press, 2017), an anthology bringing media studies and disability studies into dialog; he is also completing a monograph on early radio and the medical profession.

Maria Tallchief and Eric Bruhn, 1961. (Public Domain: see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maria_Tallchief#/media/File:Maria_Tallchief_and_Erik_Bruhn_1961.png)

Ad for WLS’s National Barn Dance, 1932 (Copyright status unclear, but this image is floating around the internet and our usage qualifies as “fair use”)